With the Berlin Peace Congress, which brought together representatives of the great powers from June 13th to July 13th, 1878 to discuss resolving the Eastern Question, the Principality of Serbia gained independence and territorial expansion in the form of four districts: Niš, Vranje, Pirot and Toplica. The relative success of the Principality in Berlin is a consequence of the mission of Jovan Ristić, Minister of Foreign Affairs, in early June 1878, and negotiations he held in Vienna with Gyula Andrássy, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Austria-Hungary, in Vienna. At that time, Serbia undertook to conclude a trade agreement with the neighboring monarchy, that Serbian and Austro-Hungarian railways would be connected within three years, and that official Vienna would bear the burden of regulating Đerdap. Perhaps even more important is the personal letter of Prince Milan, which Ristić handed over to Andrássy on that occasion, and which represents the starting point for the consistent Austrophile policy of the young Serbian ruler. The prince’s austrophilia can also be seen in the change of Ristić’s government in 1880 on the issue of the trade agreement with Austro-Hungary and, even more, in the conclusion of a political agreement, the Secret Convention June 16th/28th, 1881, with the same Great Power. With the letter of the Secret Convention, Serbia refrained from any moves against its powerful neighbor and would not conclude agreements with foreign countries without a previous agreement with Austria-Hungary, and in return received a vague promise that it could expand territorially at the expense of the Ottoman Empire and support for the proclamation of the kingdom.

Although Prince Milan received guarantees from the neighboring monarchy that Serbia would become a kingdom, the very moment of the proclamation was motivated by the reasons of domestic policy. As early as January 1881, a contract for the construction of a railway was signed with the great Parisian financial institution General Union and Eugene Bontou, backed by Vienna’s Lenderbank and Austro-Hungary. However, in January 1882, the mentioned institution went bankrupt, which caused great excitement of the Serbian audience. News of the damage the state suffered with the fall of Bontu diminished the reputation of the progressive government and the Prince of Milan and provoked an interpellation and obstruction of radical parliament members in the assembly. In an attempt to somehow quell the disgrace, the progressive government, instead of resigning itself, proposed to Prince Milan to declare Serbia a kingdom and himself a king. After hesitation, encouraged by the increase of the civilian list, the prince agreed.

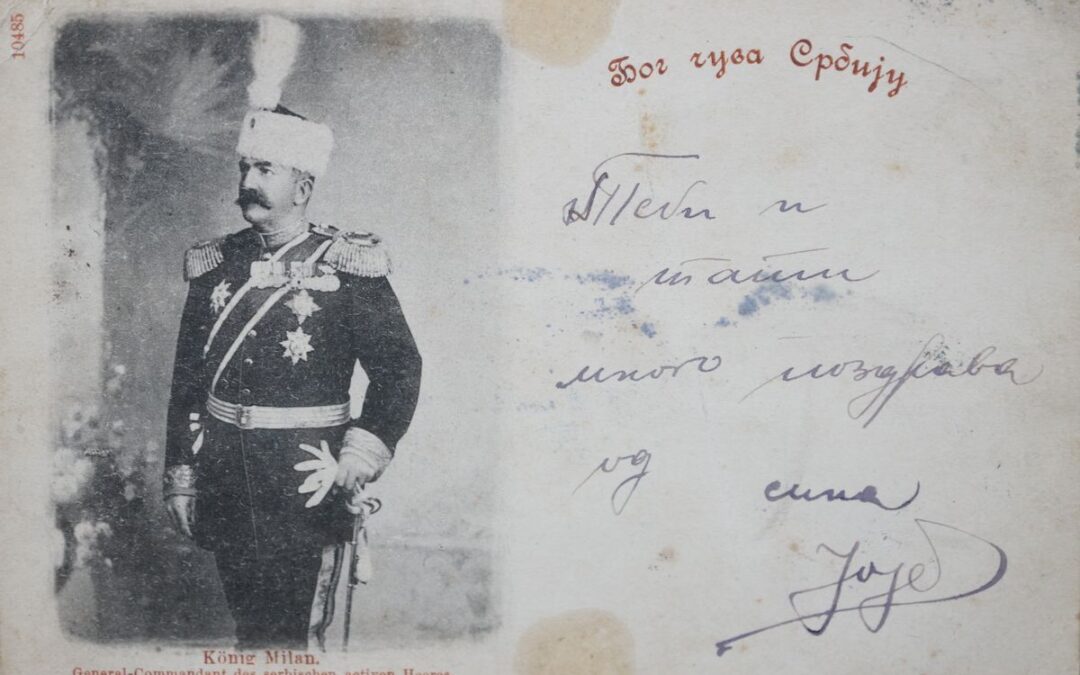

The Principality of Serbia became the Kingdom of Serbia on March 6th, 1882, according to the new calendar, and February 22nd, according to the old calendar. According to the testimony of Slobodan Jovanović, this important date was marked by platoons from the Belgrade Fortress. The whole town was decorated with flags, the circle was played in the middle of Terazije, and the young king honored the parliament members in the court. After the proclamation of the Kingdom of Milan M. Obrenović IV received congratulations and deputations from all over the country.

Congratulations to King Milan were also sent by the official representatives of the town of Karanovac: the head of the Karanovac district Nikola Antić, the acting president of the Karanovac municipality Sreten Krsmanović, a member of the municipal court Mihailo Čebinac and all members of the municipal board. The congratulations sent by the representatives of the trade guilds of the trade-tailors and charugija (opančar) emphasize the desire to hold the official coronation ceremony of the first modern king in the Žiča monastery, where seven Serbian kings were crowned.

Darko Gučanin

historian, archivist

Director of the National Museum Kraljevo