On Midsummer’s Day, July 1899, at the entrance to Knez Mihailova Street, four revolver shots were fired at an open car in which Milan Obrenović was riding. The former king received only a superficial wound, and the failed assassin, Stevan Knežević, was soon caught. The question arose in whose favour and on whose behalf he acted. The assassin identified retired colonel Vlajko Nikolić and Podrinje district chief Živko Anđelić as the organizers and instigators of the assassination attempt. However, Milan Obrenović believed that behind everything was his old enemy, the Russian Empire with its secret police and exponent of its interests in Serbia, the radical party. That’s why Pašić, along with several influential party comrades, was detained the same evening. The fight against radicals from the people who were dismissed from service, imprisoned in their homes, or expelled from the country also began. Soon after, the creation of a special high court for the town of Belgrade and the Danube County was announced, despite loud protests from the foreign public.

The trial at the High Court for the high-treason enterprise and the assassination of Milan Obrenović began in the first days of September 1899. In the indictment, only the guilt of the immediate perpetrator, Stevan Knežević, was unequivocally established. The participation of the Russian secret police in the assassination and the connection of the assassin with the most visible radical politicians could not be proven. King Milan tried to have Nikola Pašić and Kosta Taušanović sentenced to death, at any cost, but under pressure from Vienna and Petrograd, that was abandoned.

The judgment of the Supreme Court was pronounced on September 25th, 1899. Stevan Knežević and, in absentia, Ranko Tajsić were sentenced to death. The other conspirators were sentenced to twenty years in prison. Pašić and Taušanović were separated from the high treason trial and sentenced to five and ten years in prison, respectively. Pašić was soon pardoned. The trial and the decisions of the Supreme Court caused indignation of the domestic and foreign public, dissatisfaction of the Serbian intelligentsia, a general feeling of insecurity and reduced, already well underway, the reputation of Vladan Đorđević’s cabinet, the Obrenović dynasty and the former king.

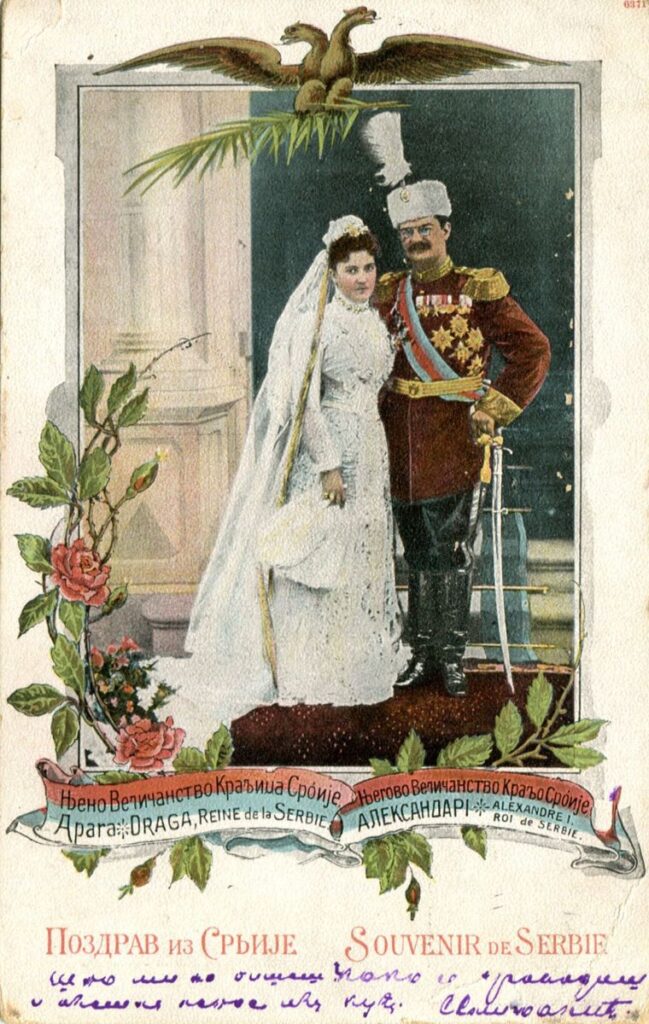

The Marriage of King Alexander

The marriage of the young King Alexander Obrenović was an extremely important dynastic, diplomatic, and political issue. Over the years, numerous governments and politicians have dealt with this problem, but, above all, the king’s parents, each from their own angle and account. Queen Natalie wanted her son’s marriage with a Russian and later a Montenegrin princess, which would bring about a turn of foreign policy in the direction of Russia, and former King Milan with a German princess, which would bind the Kingdom of Serbia to the Triple Alliance. After the Midsummer assassination, it seemed that there was a danger for the future of the Obrenović dynasty, so plans were made for the marriage of the young ruler to the German princess Alexandra of Schaumburg-Lippe. There was another reason. Milan Obrenović noticed his son’s many-year attachment to Draga Mašin and planned to end it by marrying him, avoiding an open conflict. He seemed to have succeeded, when in June 1900 the former ruler, armed with a special written authorization from the king, was tasked with completing the preliminary negotiations with the Schaumburg-Lippe family.

While Milan Obrenović was abroad and preparing his son’s marriage, Alexander, in mid-July 1900, was preparing for his wedding with Draga Mašin. The young king feverishly tried to secure the support, with not much success, of court officers, generals, and members of the government. Determined to marry his mother’s former court lady, Alexander explained his plans to his father in a letter on July 19th, and the very next day his engagement was announced. Upon the official news of the engagement, the former ruler submitted his resignation from the position of commander of the active army, as he did not approve of his son’s marriage. However, it was expected that Milan Obrenović did not say the last word on this matter and that he would appear in Belgrade, which, knowing his influence on the army, could be embarrassing for the newly engaged couple.

The old king immediately left Carlsbad for Vienna to seek support. He was informed by the official, authoritative Austro-Hungarian circles that his arrival and subsequent actions in Serbia could be interpreted as the interference of the Habsburg Monarchy in the internal affairs of another country, so support was absent. The former king lost the will and courage to take action. Milan Obrenović truly loved his son and was deeply hurt and defeated by his marriage to Draga Mašin. But without composure and determination to take serious steps, Milan was only left to grieve over his and his son’s fate, distraught by parental pain.

The Death of Milan M. Obrenović IV

Milan Obrenović settled in Vienna. There was a fear of his return to Serbia, and at the end of July 1900 it was ordered that the former ruler was forbidden to return to the country, and if he did not deviate from the border, he was to be escorted under guard to Belgrade, and then to Knjaževac. The Belgrade press frequently attacked Milan Obrenović, the National Assembly condemned his role in the regime he created, and he was kept under surveillance, above all, by the Russian and Serbian secret police. But there was no need for that, the former king was broken. Having no other income until the appanage from Serbia, without the strength to resist, he looked tired, pensive, insecure. Dejected and desperate, he led an empty life in Vienna, interrupted only by rare entertainment, which he did to relieve his heavy thoughts.

At the end of January 1901, Milan Obrenović fell ill with influenza. Kosta Hristić, the Serbian representative in Austria-Hungary, informed King Alexander on February 8th that the disease had reached dangerous proportions. The representative received an order from the young king to go to Milan to express his hope for his speedy recovery. Although Hristić reported the next day that the condition of the former ruler was critical, Alexander did not travel to see his father for the last time, but Colonel Lazar Petrović was sent to Vienna. Without meeting his son, after agony, Milan Obrenović died on February 10th, 1901, between four and five in the afternoon. He was laid on a bier in a red general’s uniform with the star of Miloš the Great, an icon and rosaries. He was buried, according to his own wish, in the Krušedol monastery, on Austro-Hungarian land, at the expense of the emperor, although King Alexander requested the body of his father in order to bury him in Belgrade with all honours. The young ruler did not visit Milan’s grave until two years later.

In the End

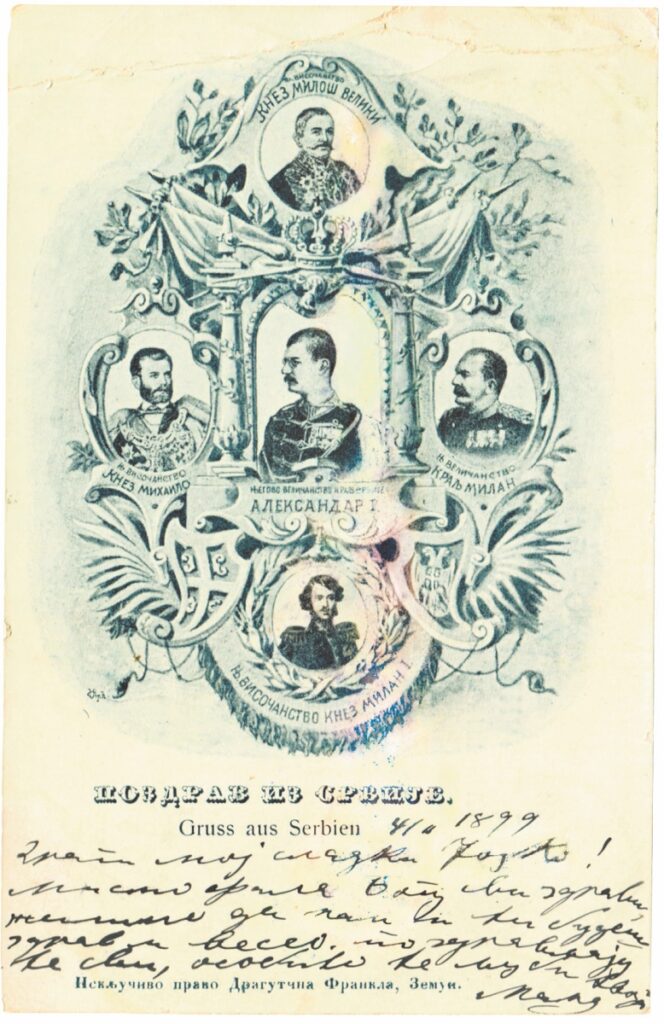

The personality and work of King Milan M. Obrenović IV intrigued both contemporaries and later researchers and public opinion. Brought to the throne as a fourteen-year-old spoiled but extremely bright boy, Milan Obrenović developed into an intelligent ruler who was only prevented from reaching the heights of his own talent by a lack of personal courage and a timid, weak-nerved nature. Whatever we think about the first Serbian king of the new century, however much we consider his flaws, weaknesses, political and personal mistakes or list his undoubted virtues and successes, we must not lose sight of a few facts. During the government of Milan Obrenović, Serbia went from a dependent state within the Ottoman Empire to an independent, constitutional, parliamentary kingdom with an organized army and railways, a National Bank and a compulsory primary school. Although he was probably the least patriotic of all the Serbian rulers in the 19th century, his activity prepared opportunities for the realization of great national goals in the later decades. On the other hand, Milan Obrenović will be remembered as the ruler who renounced, as an Austrophile beyond any reasonable measure, Bosnia and Herzegovina and who, after the military defeat, left the championship in the Balkans to Bulgaria. It should also be mentioned that this rarely perceptive politician, but also a hot-headed one, a gentle father and husband, but also a voluptuous person, commander of the active army, but also a lover of city pleasures, led three wars, suppressed the Timok Rebellion, survived a series of assassinations, entered the conquered Niš victoriously, defeated and left Slivnica, he agreed with the change of the Constitution in a liberal spirit, but also stained his hands with the blood of his opponents.

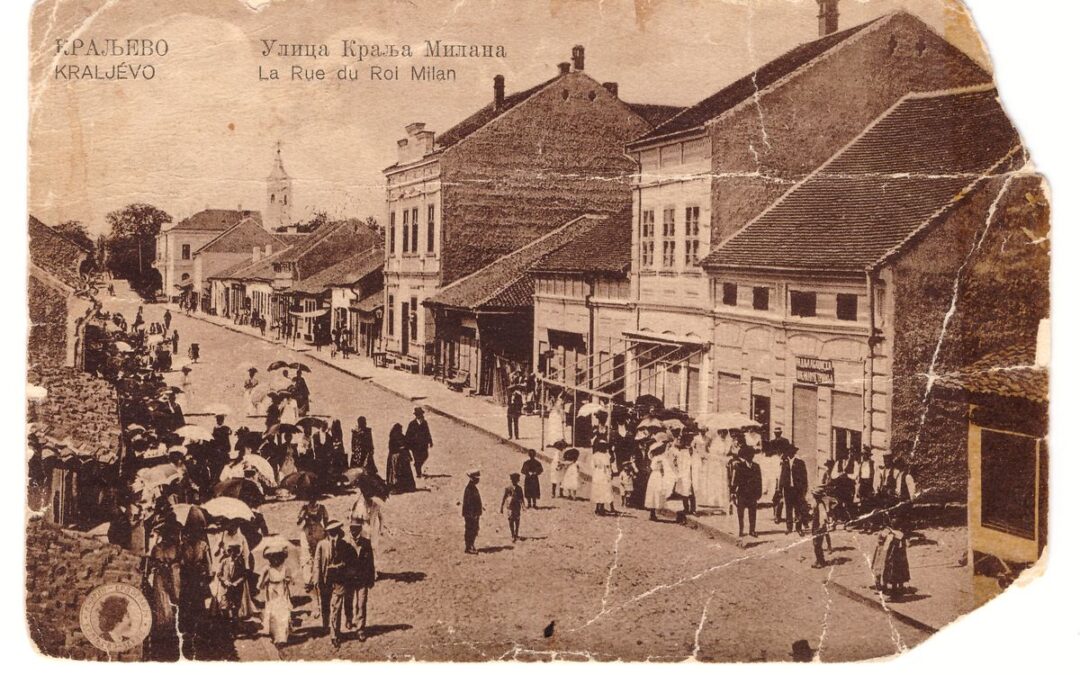

We hope that in these twelve episodes the life and fate of Milan M. Obrenović IV, the ruler during whose administration the Agricultural School in Kraljevo was founded and the Turkish name of the town was replaced by the name that the town, in truth, has been proudly carrying for 140 years.

Darko Gučanin

historian, archivist

Director of the National Museum Kraljevo